As a pre-med student at the UW, Leonardo Diaz joined a lab in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) to get experience doing research. In the process, he made a discovery that could inspire some of the first pharmaceutical treatments for autism.

.png)

For the past three years, Diaz has been working with DEOHS Assistant Professor Yijie Geng as a trainee in the department’s Supporting Undergraduate Research Experiences in Environmental Health (SURE-EH) program. The program provides paid research opportunities and mentorship for undergraduates at the UW, including those from groups underrepresented in the biomedical and behavioral sciences, with funding from the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Diaz, a first-generation college student, was drawn to Geng’s lab because of its focus on understanding how molecular interactions impact social behavior, particularly in autism.

“As someone who would like to go into medicine and aspires to become a pediatrician, I think autism is one of the biggest challenges in adolescent health right now,” Diaz said.

Environmental chemicals and autism

When Geng joined the DEOHS faculty in 2022, Diaz became the first member of his lab. The lab investigates how chemicals in the environment impact social behavior in people with autism by using zebrafish as a model of human sociality. Nearly 40% of autism risk has been attributed to environmental factors.

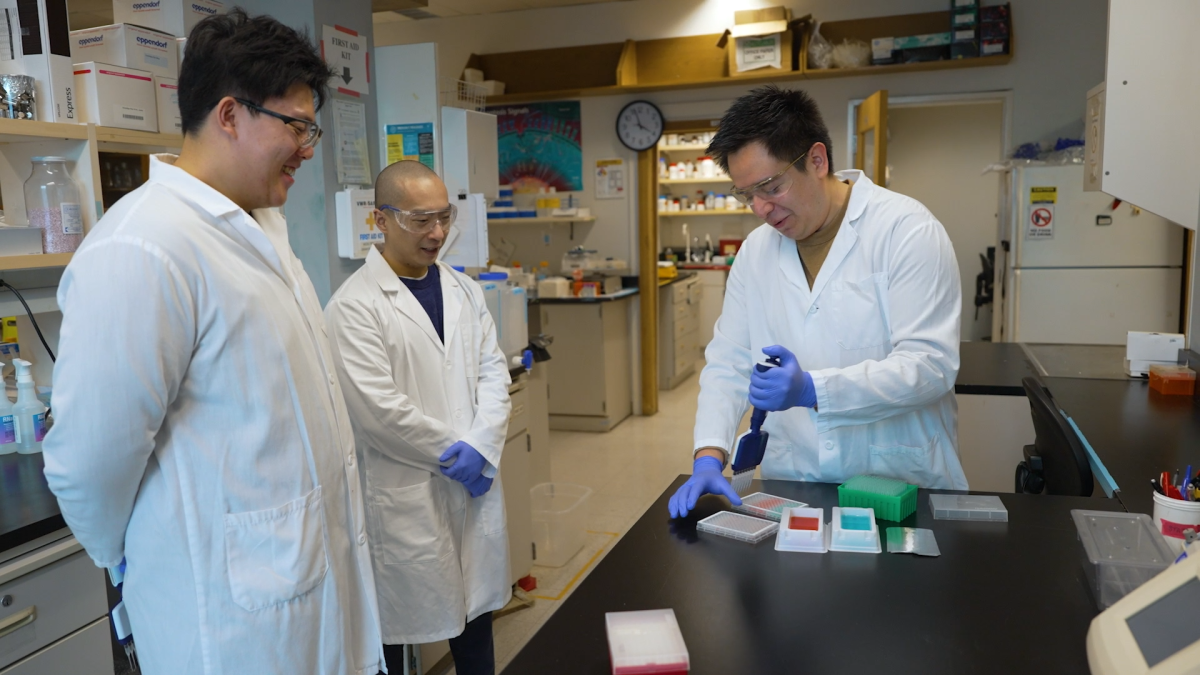

DEOHS Assistant Professor Yijie Geng studies how environmental chemicals affect social behavior. He and his lab members are trying to discover metabolites in the gut microbiome that can modulate autism risk and behavioral symptoms. Source: SOT TV.

Typical zebrafish, like people at a party, tend to move toward one another. With a system that can screen more than a thousand zebrafish a day, called Fishbook, Geng and his lab members test how various chemicals may disrupt this behavior. They have identified several that lead to reduced social interest similar to symptoms of autism in humans.

One of them is the pesticide chlorpyrifos, known for its toxicity to honeybees. When Diaz and Geng treated zebrafish embryos with the chemical, they swam around haphazardly after growing up, seeming to ignore their fellow fish.

A promising pathway

The researchers thought that if they could find molecules that would reverse this effect, it could inspire new ways to treat autism. After screening many options, Diaz hit on a small molecule naturally produced by bacteria in the human gut, called butyrate. It restored the social interest of zebrafish treated with chlorpyrifos.

But the researchers also wanted to understand why this was happening. After months of work, including using a gene editing method called CRISPR to disrupt certain genes, Diaz showed that butyrate produces this impact by inhibiting a class of enzymes called histone deacetylases.

Then, by examining the brains of the zebrafish, the team showed how chlorpyrifos might influence behavior: it suppressed many genes expressed in neurons, including some associated with autism in humans, and elevated the expression of genes that regulate circadian rhythms. Again, butyrate reversed some of these effects.

The results suggest that butyrate or other histone deacetylase inhibitors could have promise as a therapeutic for social deficits in autism, at least for cases linked with environmental exposure to chlorpyrifos.

Mentoring future scientists

Geng and other mentors see the SURE-EH program as a way to help their trainees learn how to make their own scientific discoveries. “We treat them as independent researchers,” he said.

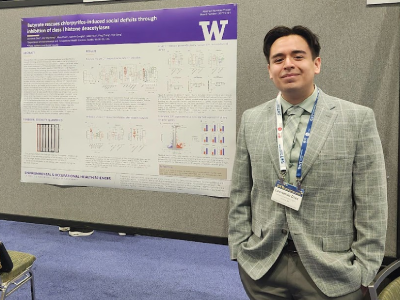

Diaz, Geng and their collaborators recently published a preprint about the discoveries in bioRxiv, and also filed two patent applications related to them.

Last year, Diaz and research scientist Ally Kong, also in Geng’s lab, won first place in the graduate student category when they presented preliminary results from the project at the Society of Toxicology’s Pacific Northwest Association of Toxicologists (PANWAT) annual meeting.

“It was like a lightweight winning a heavyweight championship,” Geng said. “Very few undergrads would be able to achieve this.”

During his many hours in the lab, Diaz finds fulfillment in “seeing step by step results,” as well as building a foundation for his future.

“The program and the lab have not only solidified my commitment to see myself in a career in medicine, but also to continue to work at the intersection of research and medicine,” Diaz said. “I really think that research can drive meaningful improvements, especially on the side of public health.”

A new fish facility open for collaborations

Geng’s ultimate goal is to screen over 4,000 environmental toxicants that have been suspected by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to negatively impact public health.

_0.png)

“No one has comprehensively assessed those chemicals for their impacts on social behavior and autism,” he said.

Baixi (Alex) He, a PhD student in Geng’s lab, is leading this large-scale screening project. So far, he has screened 150 chemicals and found some promising leads.

Geng’s newly renovated zebrafish vivarium can house about 30,000 fish, with capabilities in high-throughput screening for behavior, toxicity, drug discovery, and disease modeling. When it opens in spring 2026, he hopes to engage with collaborators at the UW and outside partners from academia or industry who might have an interest in using the facility.

“We have more than enough capacity to support not only our own work, but also our colleagues,” Geng said.